During the Polish-Ukrainian war that began on November 1, 1918, on the night of November 21-22, Polish troops knocked out Ukrainian units from Lviv, which had controlled the city for about three weeks, and took full possession of the city. Shortly thereafter, the Lviv Pogrom took place, which lasted more than two days (until November 24, 1918). It involved mostly Polish soldiers and officers, as well as civilians, including women.

According to various eyewitness accounts, including that of attorney Tobias Ashkenaze, founder of the Jewish Committee for the Victims of the Lviv Pogrom, Red Cross nurses were also directly involved in the crimes. According to Ashkenaze, a total of 14 nurses were involved in the pogroms. Sali Zonntag, a Lviv resident, recalled that one of these Red Cross nurses urged the soldiers to shoot her relatives during the pogrom. In the end, the pogromers killed her older sister and her husband and her younger sister, who was only 14 years old.

The pogrom began at about 6 a.m. on November 22 on Bużnicza Street, named after the synagogue and located in the heart of the city’s Jewish quarter. At that moment, Dąbrowski’s Mazurka (the future Polish anthem) began to be played there, to the sound of which Polish legionnaires (Polish armed forces established in August 1914 in Galicia shortly after the outbreak of World War I) began to loot Jewish stores and houses in this and nearby streets. The first attacks on Jews and looting of houses in Krakowska Square took place. Around 8 a.m., the soldiers, in the presence of their commander, Lieutenant Roman Abraham, and in front of the gathered crowd of citizens, began to smash Zipper’s jewelry store, the largest and richest store in Lvov, on the Market Square. For the military and the crowd, this was a clear sign of the legalization of robbery and violence against Jews.

After receiving this signal, the soldiers and civilians began to loot all the Jewish stores in the Market Square. On Krakowska Street the pogromists went towards the Jewish quarter and on the way they also looted all the Jewish stores on that street. The soldiers shot through the windows of the stores and apartments and began ruthlessly looting the very homes of the Jews under the guise of searching for weapons. In fact, they wanted money, jewelry, and also wanted to take revenge on the Jews for allegedly taking the side of the Ukrainians, shooting and throwing axes at Polish soldiers and dousing them with boiling water (according to eyewitnesses, this is how the pogromists explained their actions). “The leader of the raiding groups, a legionary with an armband said to me, ‘We have orders to destroy all Jews, starting with a two-month-old infant.’ The same Legionnaire also showed me a printed piece of paper with an alleged order to kill Jews,” recalled Caroline Klang, who managed to survive. The pogromists said the authorities gave them 48 hours to loot and kill Jews. “Colonel Sch., seeing a child in one apartment, grabbed him and shouted: “Why so many Jewish bastards?”. He wanted to smash that child’s head against the wall. The unhappy mother barely saved him,” reads the testimony of another eyewitness.

All these crimes took place with the full connivance of the Polish military authorities, who had just gained control of the city. At 9 a.m. on November 22, 1918, the commandant of Lvov, Lieutenant Colonel Czeslaw Monczynski, arrived by car in the center of the city. On Market Square, he watched the pogrom with a smile and did not interfere in any way with its participants, one eyewitness noted.

At 10-11 a.m. the leaders of the Jewish community, Dr. Ozyash Wasser and Dr. Emil Parnas, appealed to General and commandant of the Polish army in Eastern Galicia, Boleslaw Roja, a close associate of Polish commander-in-chief Józef Piłsudski, to stop the pogrom. Upon hearing them, Roja became horrified and issued an order to immediately impose a state of emergency and military courts in Lviv and handed it to the delegates to deliver the document to Monczynski. Wasser and Parnas had to wait in the reception room of the commandant of Lvov for several long hours, during which the atrocities against the Jews continued. At the same time, Monczynski, who was a Polish nationalist and anti-Semite and who had personal scores to settle with Roy, threw them out, refusing to carry out this order. That same evening Roja sent a telegram to General Tadeusz Rozwadowski, to the military headquarters in Kraków and to the district headquarters in Peremyshl: “In Lvov there are robberies and murders of drunken mobs.” He reported that he needed additional infantry and lancer units to take control of the situation in Lviv.

Meanwhile, the pogrom continued, with military trucks and Red Cross cars circling the streets of the Jewish quarter, on which the pogromists piled the stolen goods. Around 4 p.m., a Red Cross car arrived, in which sat four orderlies. They noticed that the robbers had left one store untouched, so they themselves broke in and completely emptied it. The merchant Mauricius Ignacius Baches saw Polish officers on horseback riding through the streets during the robberies. They would shoot in the air and shout that robberies were forbidden, but then add: “Don’t be afraid, we are shooting in the air. You can go on robbing Jews!”.

The pogrom was attended not only by soldiers, but also by intellectuals, people with “good faces,” including women in elegant clothes, coats, hats, veils and gloves, accompanied by servants who helped them carry away loot from Jewish homes and stores. One witness recalled the following scene: “On Skarbkowska Street, a woman in a hat was arguing with a soldier because he had taken too few dresses from the store. Especially one [dress] he was holding in his hands was slightly torn.” And Adele Neuer, a victim of the pogrom, said that one of the Polish legionnaires, after shooting her brother, sat down at the piano and played it for 1.5 hours, while the other two soldiers danced at the same time. “Apparently, the killer was an intelligent person from the upper class, as I, who played the piano, found the game interesting,” she reported.

Rioters who broke into the Lvov City Hall attempted to lynch the city’s vice-president, the Jew Philip Schleicher. This was avoided only after the entire Lvov city council, composed predominantly of Poles, resigned. Throughout the first day and until late at night, murders and abuse of Jews, robberies, rapes and arson took place. Houses in the Jewish neighborhood burned. In most cases, the soldiers forbade putting out the fires and prevented people from leaving the burning houses by shooting at them with rifles. Representatives of the fire department told the Jews that they could not help them in any way: “I don’t have any water for you”.

On the night of the first day of the pogrom, the perpetrators set fire to the Tempel synagogue in the old Market Square. In all, at least three synagogues and about 100 Torah scrolls were burned completely during the pogrom. Three young Jews who tried to save the holy books were shot by Polish soldiers. “The crowning achievement of the atrocities and inhumane atrocities was the abuse in Jewish houses of worship and synagogues. <...> In the old synagogue on Buzhnichaya Street the safe was broken into and gold and silver religious objects of high historical and cultural value were stolen. About 50 scrolls were thrown into a pile, doused with kerosene and set on fire. Several Jews, including a high school student, jumped into the fire to save these holy objects and died in the blaze,” wrote the Jewish newspaper Shwila. – The arsonist soldiers thwarted any attempt to save [the holy books], shooting at the rescuers and killing, among others, a high school student whose charred corpse with a Torah scroll under his arm was later discovered.”

On the morning of November 23, the pogrom in the Jewish quarter resumed and lasted until the end of the day. On the walls of Lvov appeared a proclamation of the city staff (i.e., Lieutenant Colonel Monczynski) to the Jews of the city, in which they were accused of hostile behavior toward the Polish troops. This appeal justified the aggression of the Polish population against the Jews.

In the afternoon of the same day, the Polish military intervened for the first time to stop the pogrom. They made the first arrests of the participants in the pogrom. At 18.45 General Roja reported in a telegram to Krakow that the action to pacify the city was “progressing”. But in a subsequent telegram he warned that complete pacification of the city and surrounding area “by neutralizing the looting gangs” could not be achieved without reinforcements. “Owing to the delay in the delivery of 4 p.p. and cavalry, decisive intervention and cessation of violence are ruled out,” he wrote.

At 7:30 a.m. on November 24 (the third day of the pogrom), Polish soldiers fired rifles in Kraków Square to prevent two Jewish passersby from helping a Jewish woman trying to escape from a burning house. Her fate is unknown. This is one of the last recorded acts of pogrom.

On the same day, a new order appeared on the walls of Lvov by the commandant of Lvov, Monchinsky, to introduce field courts of simplified procedure, which provided for the death penalty for people found guilty of robbery and rape. Three people were sentenced to death for murdering Jews, and 73 others were sentenced to death for participating in robberies. Most other cases against pogromists fell apart due to lack of evidence. Monchinsky also imposed a curfew in the city and ordered the commandant of the Lviv garrison to immediately begin clearing the city, especially the Jewish quarter, of armed men, both military and civilian. In case of resistance, he instructed the use of firearms.

The acute phase of the pogrom, in which people were beaten, maimed, killed and burned alive, as well as looted, lasted little more than the same 48 hours.

Sources:

- Grzegorz Gauden, Lwów – kres iluzji. Opowieść o pogromie listopadowym 1918 (Lviv. End of illusions. An account of the November 1918 pogrom). Kraków, 2019.

- Documents published in the Evidence section.

The testimonies are mostly translated from Polish, in rare cases from German. Data on the number of victims in different documents may differ. In the “Events” and “Victims” sections, the number of victims is given according to the documents that, in our opinion, provide the most reliable information.

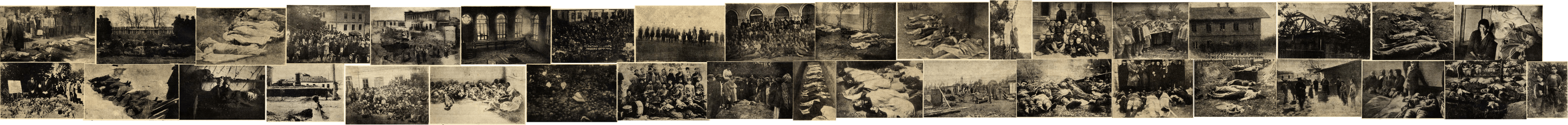

City and Regional Headquarters (November 23, 1918):

“During the three weeks of the battles for Lvov, the Jewish population not only did not remain neutral towards the Polish army, but often resisted it with weapons in their hands, and treacherously tried to stop the victorious march of our troops. Cases of shooting at our soldiers from ambushes, dousing them with boiling water, throwing axes at patrols, etc., have been established.

The command of the Polish army suppresses the natural impulse of the Polish population and army [to take revenge on the Jews] …. All citizens, regardless of religion, are under the protection of the law. In this regard, an order for courts and fines was issued.

Nevertheless, the Jewish population as a whole has a legal obligation to assume responsibility for a part of its co-religionists who continue to act as if they wished to inflict a previously unprecedented catastrophe on the entire Jewish population. The Polish Army Command expects the Jewish population of Lvov, above all in its own interest, to discourage manifestations of hatred against the Polish authorities, to behave loyally and to help the authorities to establish and maintain lawful order.

Jakub Lejka:

“The attack lasted half an hour, the soldiers were armed with revolvers and hand grenades. They threatened: ‘You poured hot water on the Legionnaires, you were militiamen! If you give [your] money, we will let you live.”

Zelig Vagshal:

“The gang [of pogromists] threatened us: ‘We will show you, you poured [hot] water on us and shot at us. You were fraternizing with Ukrainians, with this criminal”.

Moses Jozef Acht (December 5, 1918):

“On November 22, 1918, at 10 a.m., 3 non-commissioned officers in the uniforms of Polish legionnaires [who were] 25-27 years old, from among the intelligentsia and academics, entered the apartment. They threatened with revolvers because the Jews were on the side of the Ukrainians.”

Izak Vainshtok, merchant (lived at 34 Slonechnaya Street), Yetka Vainshtok:

“On Friday, November 22, 1918, at 11 a.m. 4 legionnaires came to me, ordered me to put my hands up, demanded money and took 400 crowns. The same day in the evening three other armed legionnaires came, and on November 23 the legionnaires robbed all day long. One legionary who came to [my] neighbor, Mrs. Fruch, stated that they were allowed to rob and kill Jews for 48 hours.”

Berl Goldstaub:

“The first attack lasted half an hour, the second a quarter of an hour. The patrol officer threatened with a revolver and shouted: “You shot at us! You have guns.” The victim was also beaten on the head. Leaving, the legionnaire warned: “Wait, that’s not all, they will come at night [to you].” On Friday [November 22, 1918], at 10 p.m., the victim ran away to his neighbor on the third floor and does not know what happened next [in his apartment]. Because of the fire in the neighboring houses, there was stuffiness in [his] house. When [tenants] wanted to escape through the gate on Saturday evening, [soldiers] shot at the gate and shouted, “You can’t go out, you’ll burn there!”.

Caroline Klang

“The leader of the raiding groups, a legionnaire with an armband told me, ‘We have orders to exterminate all Jews, starting with a two-month-old infant.’ The same legionnaire also showed me a printed piece of paper with an alleged order to kill Jews.”

Mojesh Weinreb:

“Six men burst into the apartment, military men only, with 4 [of them] Legionnaires in Maciej jackets (including 1 Zugeführer) and 2 Polish soldiers in Austrian uniforms, all men from the upper classes. At the bottom stood an officer in Austrian uniform, well known to me, and directed the whole operation. At about 8 a.m. on November 22, 1918. Six soldiers came to me, and the Polish army was standing around the house. They said, “Now it’s your turn, give me the money.” And started robbing, beating me and my son with rifle butts. Another Legionnaire on the street told me on 22.11.18 that they were allowed to do whatever they wanted to Jews. I know this legionnaire.”

Mohel Kessler:

“The attackers shouted: ‘Thank God we are not killing you. We came to the Jews who wanted to kill us. Now we have the right to kill you.”

Dr. Max Schaff:

“I reside in Lviv on Ochronek Street, 11 a. On November 22 of this year I learned that at 8 a.m. the Poles entered the city, and [as early as] 6 a.m. looting began in the Jewish quarter. In order to find out the state of affairs, I went to the city and found that the jewelry stores of Vishnitz and Zipper were looted in the Market Square. At that time a military guard was already standing near Zipper’s store.

A machine gun was set up at the end of Krakowska Street, with an officer and 6 soldiers standing next to it. In my presence, [this] machine gun was loaded, i.e. a belt with cartridges was taken out of the box and the gun was loaded with them. The soldiers and the officer, who was called “Mr. Colonel” had a bandage on his hands in the shape of a dead man’s head. Less than 8 steps away from the machine gun, Polish soldiers looted Jewish stores, while Catholic stores, such as those of P. Mokrzycki, remained untouched.

I saw soldiers shooting the shutters with rifles to open the stores. Goods were thrown out of all the stores. The soldiers first scored the goods and only then let in a crowd of people who were also looting Jewish property. I saw legionnaires with very handsome intelligent faces, indicating a good origin and an intelligent profession, carrying away whole rolls of materials and fabrics.

Picturesque scenes took place in the street. A soldier in an Austrian uniform with the insignia of a field officer and a revolver in his hand enforced “order” by stopping those who took too much from the Jewish stores and dividing it among those who got nothing and could not get into the stores because of the large crowd. There were no police or security forces to be seen anywhere. Everywhere the looting was led by soldiers with rifles and hand grenades, they looted themselves or encouraged the Catholic public to participate in the looting. On Skarbkowska Street, a woman wearing a hat argued with a soldier because he had taken too few dresses from the store. Especially one [dress] that he held in his hands was slightly torn.

The next day, November 23, the picture did not change at all. On Grodzicki Street, I witnessed Polish soldiers trashing a restaurant. They entered [this] restaurant in groups, not allowing civilians in, claiming that it was vodka for the soldiers.

The next day I went to Mr. Czynsz Diker, an 80-year-old old man, on Marcin Street. He was robbed in his own apartment, [the attackers] were shooting, one bullet grazed the forehead of Fanny Diker, a 78-year-old old woman, leaving her eye bleeding and swollen for several days. In the same house at [ul.] Marcin 9, almost all the Jewish tenants were robbed, but not a single Catholic tenant was robbed. 12 soldiers and 2 officers attacked my relatives, Leon Felix, 7 Szcznieżna St., and took from my relatives all the cash they had on them. In the apartment of my cousin Solda, these soldiers sat down to eat, having requisitioned a Saturday lunch for that purpose. When they saw the gramophone, they ordered it to be turned on. One of them is the son of a letter carrier who lives on Marcin Street; he knows Ms. Soldova (wife of Sold’s cousin – website editor’s note), who has lived on that street since childhood. I could not persuade Mrs. Soldova to give me the name of this soldier because she was afraid of reprisals from him and also from his comrades.

I am prepared to swear that the above testimony is true, and I would also like to point out that on [Kar. Ludwik, 3rd of May, Akademicheskaya, all the two days mentioned above, the Polish public spoke only of these robberies, and several women noted with satisfaction that no Jews were seen on Korsa (a district in Lvov – website editor’s note).

David Stein:

“On his way home on November 23, he noticed that many people, especially railroad workers, were walking toward the city shouting, ‘We are going to kill the Jews.'”

Proceedings of the Central Jewish Relief Committee:

“One officer who rode at the head of the Polish cavalry into the gate on Zelenaya Street confirmed to the women who applauded him, ‘We have dealt with the Ukrainians, and now we are going after the Jews and will slaughter them like pigs’

“P. L. heard how in a group of soldiers walking down the street, one of them griped loudly: ‘We took an oath that each of us would kill at least two Jews.’ Another group [of soldiers] passed by humming a Krakowiak motif: “Show me, show me a rich Jew, I’ll let the guts out of him.”

“Colonel Sch., seeing a child in one apartment, grabbed him and shouted: “Why so many Jewish bastards?”. He wanted to smash that child’s head against the wall. The unhappy mother had a hard time saving him.”

“In the synagogue on Bužníče street “CHADUSZYM SZIL” gathered approx. 70 people who had escaped from a gang of thieves. Soon a patrol consisting of legionnaires appeared, who let the women out and demanded a ransom of 20,000 crowns from the men. The victims could only collect a few hundred crowns in such a short time. In response, the legionnaires attached a rope to a hook and demanded that anyone present climb it.

The victim (the author of the testimony – website editor’s note) said that he would rather die by bullet than by hanging. Then they ordered all the Torahs and Talmud books to be taken to the middle of the hall, piled them in a heap and lit a fire, locking the doors [of the synagogue] behind them. It was only by chance that a hole in the wall was discovered, of which the legionaries were unaware. Through it, those doomed to death by fire were able to leave the synagogue undetected and were saved from certain death.

Original document (pp. 13-14, 24)

Newspaper materials Chwila:

“The Jewish Quarter must burn,” the pogromists said. In fact, it was the easiest way to ‘de-Jewishize Lviv’ for those who had been fed anti-Jewish literature since childhood.”

“The crown of the atrocities and inhuman atrocities was the abuse of Jewish houses of worship and synagogues. Groups of Polish soldiers set fire to three synagogues. In the old synagogue on Buzhnicha Street, the safe was broken into and gold and silver religious objects of high historical and cultural value were stolen. About 50 scrolls were thrown into a heap, doused with kerosene and set on fire. Several Jews, including a high school student, jumped into the fire to save these holy objects and perished in the flames.

Arsonist soldiers thwarted any attempt to save [the holy books], shooting at rescuers and killing, among others, a high school student whose charred corpse with a Torah scroll under his arm was later discovered. The TEMPLUM Progressive Synagogue was set on fire, but it was still saved. Several smaller houses of worship were burned or destroyed. In all, more than 100 Torahs of priceless value as religious relics and of high antiquarian and scientific value were destroyed or burned.”

World Zionist Organization spokesman Israel Cohen:

“Three separate attempts to set fire to the Liberal Synagogue because the Poles claimed there were machine guns: three Torah scrolls were completely destroyed, two were damaged. In the rabbi’s changing room, 5 tin cans of gasoline still lie on the floor. The old Vorstädtische synagogue (300 years old) was burned down, 36 [Torah] scrolls were destroyed, many of them were brought from Spain. A large safe was broken into, gold and silver jewelry stolen. One Torah scroll was pierced with a bayonet in several places. The third synagogue (Chiddushim) was completely destroyed: charred fragments of prayer books and Pentateuchs still lay in the snow.

I was told that machine guns were used to control the streets to prevent Jews from escaping.

After the great pogrom of November 22-23, there was a smaller scale attack [on the Jews] on December 29-30, 1918. The extensive destruction was mainly the result of a punitive operation by Polish troops, supported by the Blacks, against the Jews because of their neutrality in the Polish-Ukrainian war. There were attacks, looting, violence, murder and arson. 73 Jews were killed, several hundred seriously wounded, 49 houses and 3 synagogues burned to the ground. Estimated damage was 100 million crowns (over 4,000,000 B.P.F.). Evidence has been gathered that the pogrom was carefully prepared.”

The text is from the book Israel Cohen, My Mission to Poland (1918-1919). Jewish Social Studies, 1951 .

Testimony of Mauricio Ignacio Bachez:

“I lived with my wife in the house at 24 Buzhnichi Street, on the corner of Smochei Street, which I managed, occupied there 3 rooms and a kitchen on the second floor. On the night from Thursday to Friday, i.e. November 21-22, we did not sleep and were on the alert, fully dressed, because, given the heavy shooting on Thursday, we were afraid of surprises at night. Already at 5.30 on Friday morning I heard through the window people playing the harmonica Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła, banging on the gate and shouting “Open the gate”. At about 6 o’clock [a.m.], when it was already a little light, I saw policemen from the Polish civil militia passing by (I recognized them by the white color of their armbands with the inscription Polska Milicya Obywatelska).

When they attacked [one] Jew, they took everything he had and beat him thoroughly. I had good theater binoculars. Then the same [pogromists] came back accompanied by several civilians, in front stood a crooked EDEK, a former bricklayer and stable assistant, pointing out the stores on Smoczej Street, and then the whole company started looting. It was already 7.00 or 7.30 in the morning. Then about 60 legionnaires (soldiers of the Polish army – website editor’s note) from Zbórzegowy Pl. arrived from the square. They saw them robbing the stores on Smoczej Street (where the legionnaires and officers entered), but they did not prevent the robbers. They returned to Buzhnichna Street and went to Zhulkiewska Street. At this time a crowd approached, in which I noticed better faces, including ladies in elegant clothes, coats, hats, veils and gloves, who stopped right in front of my windows at the corner of Buzhnicha and Smoczei Streets. I saw the legionnaires approach Smoczej Street with the crowd. After the looting, each [soldier-pogromist] gave his lady a bag [with the loot].

At 21 Buzhnichy Street, the guards of this house brought a patrol of Legionnaires (soldiers) to the house, [they] opened the gate with rifle butts, began to rob and took out bedding and other things from the house. The Polish legionnaires themselves looted here without the help of the crowd.

At about 10 a.m. I heard screaming in the neighboring apartment building at 9 Ovocova Street. I went out to the balcony and saw Polish legionnaires carrying away all the things and even beds. The crowd looted until 14.00. In the meantime, officers on horseback came to Buzhnicha Street, declaring that “you can’t loot.” They fired in the air, but immediately explained to the robbers: “Don’t be afraid, we are shooting in the air, you can continue to rob Jews”. This was repeated several times. I heard it exactly from the window, with my own ears.

At about 3 o’clock in the afternoon, the legionnaires began shooting at our gate, demanding that it be opened, and when the caretaker did not open it, five of them entered the gate [on the other side of the house]. Two stayed on the stairs, and three began to go through the apartments and, holding their rifles to their chests, demanded money. At about 4 p.m. I heard from the caretaker of the house at 20 Bužníče Street, in the nearest adjacent street, that the two daughters and son-in-law of Zonntag (Genia, her husband Zygmunt Gorne and sister Klara Zonntag – website editor’s note) had been killed there.

I noticed that all day long, trucks with soldiers and even one passenger car drove along Buzhnichi and Smochei Streets and took away the stolen goods.

At about 4 p.m., a Red Cross cart pulled by a pair of crow horses with four Legionnaires’ orderlies arrived at the corner of Buzhnichi and Smocza Streets. Noticing that one brush store had not yet been robbed, the orderlies opened the store themselves and robbed it. This is how we survived Friday, November 22 of this year.

The night passed quietly. On Saturday morning I went outside and noticed that the house at 4 Smoczej Street was on fire – the store of a merchant unknown to me was on fire. Then I observed the devastation on Smoczej and Buzhnichi Streets. Near my house at 22 Buzhnichi Street, I found that in the open synagogue printing house, four Torahs were scattered on the floor. I called the school teacher (cheder teacher – editor’s note) who lived in the house, and together with him we collected the Torahs and took them to the house at 19 Buzhnichi Street.

At about 8 a.m., shooting started on Buzhnichi Street, opposite the Great Synagogue. All the inhabitants were forced to return to their homes and forbidden to close the gates. The looting was carried out by Polish legionnaires. From my window I noticed a military truck with three barrels of kerosene and some soldiers driving from Zhulkiewska Street towards Zbozhevoy Square. Half an hour later I noticed thick smoke coming from my window, went down to the gate, looked out and noticed that the [synagogue] “CHASIDIM SZIL” was on fire, then I noticed that the Allianz, a neighboring house, was on fire.

There were Legionnaires and gangs on Buzhnichi Street. I noticed that when the tenants of house 19 Buzhnichi Street wanted to save the burning shop there to protect the neighboring small synagogue from fire, then the Legionnaires opened fire at them. 2 or 3 occupants fell to the ground. I also heard cries that the water was cut off and the fire could not be put out.

Then I saw an officer and two legionnaires <...> entered the store that had already been robbed the day before, came out immediately, and a quarter of an hour later smoke billowed upward from my house. So much so that the windows were blackened. We wanted to run out of the house immediately, but on the stairs we were blocked by legionnaires who were firing. They wounded one of us, Leib Binbund, 22 years old, closed the gate and did not let us leave. I transferred about 90 people (including many strangers), including about 50 children, 5 men and women, with the help of my future son-in-law, David Blitz, to a neighboring building on Ovotsova Street.

However, the legionnaires would not let us outside and threatened to shoot us, so we had to wait there on the stairs for about an hour. Our house started burning at 10am. At about 11 a.m. we noticed that smoke was going upwards in the house at 9 Ovocova Street. Then one Legionnaire went down to the first floor where the caretaker lived, broke the door and window with his rifle butt to allow better air circulation, and we took advantage of this to escape to Ovotsova Street, where I noticed many Legionnaires. There were maybe 100 of them with 25 officers, with sabers in their hands, with the legionnaires having their guns at the ready to fire. I heard the robbers shouting, “Stop or I’ll shoot you! You can’t come out.” I stood up and said: “Now shoot.” From there I went with my family down Ovotsova St. to the Great Synagogue, where I saw legionnaires cutting off the silver crown of the Torah with sabers and Catholic women wearing Pyrojches from the Torah on their heads.

I walked down Cebulna Street, where there was also a crowd of about 200 people. There I noticed several Catholic men with city councilors’ badges. The crowd and the Polish legionnaires were looting [houses], no one prevented them. Thus we came to Goluchowski Pl. near Sttinger’s drugstore, where a Polish Legionnaire came up to me and put a rifle to my chest [with the words]: “Who are you going to be?”. I, after a little thought, answered that I was a Pole. Then this legionnaire allowed me and my family to pass. I now often see this legionary [in the city].

In my burning house at 24 Buzhnichi Street, we had to leave the wounded Leib Binbund with his father and brother, as it was impossible to carry him from our porch to the other house <...>. I heard from Binbund’s father that when the ceilings below them began to burn, his father and brother wanted to carry him outside. However, they were not allowed to carry the wounded man outside, they only allowed the father and brother to go outside and said, “This guy can burn here.” On Sunday morning at 8 a.m. [24.XII. 1918] I found the burned body of Leiba Binbund at 24 Buzhnichi Street.

Among the legionnaires on Friday and Saturday I noticed a thief I knew, Józek Czarnecki, wearing a fieldfielder’s uniform.”

Ignacy Luft:

“On Saturday [November 23, 1918] I myself saw how on Kazhmezhowska Street soldiers took goods out of the haberdashery store and took them to the commandant’s office on Smolka Square. Based on what I heard, I assume that this was a planned pogrom, a kind of reward for the liberation of Lviv [from the Ukrainians]. There was no water to extinguish the burning houses. The fireman I asked to put out the neighboring house (I was afraid that the fire would spread to our [house] as well) answered me: “I don’t have any water for you.

Memoirs of a Lviv historian Jozefа Szczeradzk(he was 18 years old at the time of the pogrom):

“The three-day massacre. The burning of the Jewish quarter, the murders and atrocities committed there by the soldiers and armed scoundrels, the murder of old men, women and children, the unfortunate victims jumping out of the windows of the burning houses onto the bayonets of the criminals waiting for them – all this was horrifying and aroused a feeling of revulsion.

It is impossible to forget the impressions I had of driving through the Lviv “ghetto,” from the back of the Goluchowski palace to Theodore Square, a few days after the pogrom. There was still smoke there, and a pungent odor of ash and dampness emanated from the fresh ashes. The streets were littered with furniture, torn clothes, and garbage from broken shops [merchants]. The burned houses stared at passersby through window hollows.

In several places in the courtyards lay bodies not yet removed. Views that until then could only be imagined, from reading about pogroms committed against Jews and Armenians. Now they were from a horrifying reality, and later, years later, from the “blast furnace era.”

The text is excerpted from memoirs Jozefа Szczeradzkwow (Adolfа Hirschbergа) “From dawn to dusk“written in the 1950s. From the book Grzegorz Gauden, Lwów – kres iluzji. Opowieść o pogromie listopadowym 1918 (Lviv. End of illusions. An account of the November 1918 pogrom). Kraków, 2019.

Testimony of Simon Kandel, a resident of Lviv:

“On Friday morning (November 22, 1918 – website editor’s note) at 8.30 I left the house to buy potatoes, I was stopped by a patrol and forced to return home. They broke into the apartment, beat me, threatened me with rifles and revolvers. My wife’s head was smashed and my daughter’s fingers were cut off. They deliberately destroyed furniture.

At 9 [a.m.] my family and I escaped to the second floor. At 10 [o’clock] they started shooting at the windows of the house, so everyone took shelter in the back of the house. At 12 o’clock I ran to [my] daughter Dora Stauber [who lived] at 24 Rutowski Street.

At 9 o’clock on the second floor of the house, Moises Spiegel was shot dead on the stairs as he tried to escape.”

The house where Kandel lived was burglarized and burned.

Hana Katz:

“After the robbery of Ms. Bienstotskova’s store, the soldiers smashed my store, after which the soldiers and a crowd of civilians began to loot it. They robbed for two whole days. Ladies in hats came with their servants to take [to their] homes the stolen goods. The store and all the warehouses on the first floor were looted.

On Saturday morning, my husband walked up to my store and asked the officer standing there to put an end to the robbery. “What’s your name?” – he asked. When he gave his last name, the man slapped him in the face, saying: “Jews to Palestine.” People who were watching the robbery from the windows were shot at.

On Friday, at 4 o’clock one officer and two legionnaires broke into the second floor in search of militiamen who allegedly stayed here under Ukrainian rule. On the porch, the officer beat Jakub Bley with a whip and called his wife and children to watch. The soldiers took away the fur hat from the beaten man”.

Sali Sonntag (testimony recorded December 17, 1918):

“[On November 22, 1918] The gate of our house at 20 Buzhnichi Street was tightly closed, so that despite the use of hand grenades, they were unable to break through it. Then they went to Ovocova Street, 5, on which [the gate] was also very strongly fortified. However, after breaking the lock with a hand grenade, they entered the house and smashed the store, which contained 8 sacks of wheat and 3 bushels of potatoes. About 30 Legionnaires (according to other sources, about 50 – website editor’s note) broke into our apartment, some had steel helmets on their heads, all had red and white badges and spoke a western dialect [of Polish].

In our apartment, which occupied the entire first floor of the building, the following people were at that time, or rather were asleep: in bed in the first room was Lirat Novaes, who witnessed what was happening at 7 a.m. [when the pogrom began]; in the kitchen slept Mr. [Yetti] Hay, a baker who came to us with all his belongings from 27 Žrüdlana Street, where the fighting [between Poles and Ukrainians] took place, [my] older brother Jakub Zonntag, younger [brother] Mauricije Zonntag, and my younger sister, 14-year-old Klara Zonntag, who was later killed.

In the room where I was sleeping were my mother Shprynza Zonntag, Mrs. Heyova (Yetti Hay’s wife – website editor’s note) and her two daughters, and my sister Bronja Zonntag. Mrs. Heyova’s things were in the next room. My mother gave one room to her children: Zygmunt Gorne and his wife (her daughter Gena – editor’s note), who took refuge there from the shooting that took place at 9 Galicka Street.

So, the aforementioned group of three burst into the apartment shouting, “Give us the gold, the silver, the diamonds, the millions!”. They chased the men out of the kitchen, Mr. Hay and my two brothers, into the living room. Anyway, everyone ran into the living room, thinking they would get to the balcony from there. I, barefoot and in my petticoat, took my outer clothes and ran to the second floor and across the balcony to the other house. <... >

I had 36,000 crowns under my pillow, which was taken by the legionary standing next to me. The same legionary let me go because I identified myself as a Polish maid and asked him to spare my life. From that moment on, as a Catholic maid, I was free to enter and I went in and out of the apartment three times. There was great confusion in the apartment. They tore the blinds, the Persian rugs in the living room, the draperies and covers on the sofas, all present [the pogromists] looted and pillaged. Among them was a sister of mercy, of medium height, blonde, with a white handkerchief tied on her head with the sign of the Red Cross.

My brother-in-law [Zygmunt Gorne] was just putting on his shoes, and my sister [Genya] was getting dressed. A group led by a field officer and accompanied by the above-mentioned sister [of mercy] burst into this room. The fieldfebel was short

Then Clara Sonntag’s younger sister, 14 years old, ran out of the other room and knelt down in front of them, asking not to be shot. Then they killed her too, shooting her in the mouth. The next day she was seen lying in the same position with her arms crossed and blood pouring from her mouth. The married sister Gorne (meaning Genia Sonntag, who took her husband’s surname – editor’s note), brother-in-law Gorne and sister Klara died in the same way.

After committing these three murders, the same group entered the kitchen, beat [my] mother on the head with a saber, who is still lying at home [and not getting up] – my mother gave them 15,000 crowns in the kitchen. This was not enough, so they threatened to kill my brother Mauricio, who was also shot and his arm was wounded. My brother is being treated in a public hospital. [My] brother Jakub Zontag was hit on the head with the butt of a rifle, shouting “Give me the millions!”. With great difficulty – first he escaped, he was brought back and beaten – he managed to escape a second time, despite having hand grenades thrown at him. He hid in a nearby lumber warehouse, where he lay all night.

The other occupants of our apartment hid in a neighboring building, while the Legionnaires continued to rob the apartment. Then they ransacked Mr. Luft’s apartment on the second floor, then returned …. to the apartment and broke [the entrance to] our warehouse with men’s clothes, civilian clothes, military uniforms for officers, officials and students, and fur coats. With shouts of “Fuck you, we have a warehouse!” they started looting the warehouse.

In the same house, in another yard, the same Legionnaires killed one Malka Kiss and seriously wounded her two sons. They are now in the general hospital. <... >

One of them – a legionary whom my brother [Mauricius] knows personally and still sees on the street – as soon as he entered the apartment, he shouted to Mauricius, “Curva, fuck! Give back the 10,000 crowns you took for the clothes.” And my brother gave him that money. This legionnaire knew my brother because I had a contract to supply clothes and shoes for legionnaires from the NKN (Naczelny Komitet Narodowy, Polish Supreme National Committee – website editor’s note) committee in Lviv. I always came to the NKN with my brother, whom they took for my husband.

When Brother Mauricius was going to the hospital a few days later, he saw the above-mentioned man. On the way he met another acquaintance, also a Legionnaire, and asked him if he could arrest the aforementioned Legionnaire who was part of the raiding party. Then the legionnaire, whom he knew personally, <...> replied, “What can you do with him? He’s been allowed to loot for 48 hours.”

The damage sustained is as follows: Apartment looted, bedding, clothes, jewelry, a bag of silver, silver candlesticks, 3 silver chains and many valuable things. Warehouse with the above clothes at 20 Buzhnichaya Street. A store of goods for officers, students and officials at 24 Buzhnichaya St. and in the same house on the edge of …

<...> I see my [stolen] belongings on the street. I recognize officers’ jackets and coats worn by officers and legionnaires. The total amount of damage amounted to 1,500,000 kroner.”

Original documents(pp. 3-5, p. 60)

Marcus Zucker (December 11, 1918):

“On Friday, November 22, 1918, seeing that pogroms were going on all around, I begged the caretaker not to let anyone in the gate, giving him money and promising him full remuneration [later]. Despite this, already at 11 a.m. he let in Polish soldiers and civilians who were knocking on the gates, among whom I recognized a good acquaintance of our neighbor Shifra Weinshtok, the wife of a furrier, an assistant to a railway employee in a railwayman’s uniform with 3 stars, [but] I don’t know his surname myself. This railroader was the leader among the attackers. He took them to my warehouse, where they looted my 7,000 kroner worth of flour and 312 loaves of bread, as well as 20 kilograms of sugar. The attackers did not enter the building itself.

The next day the caretaker of our house disappeared, and we heard him say to his wife: “Let’s go, they will set those Jews on fire today. Why should we be responsible for the Jews shooting at ours?”. We heard the rumbling of the cars in which the stolen property was being taken away and from which the soldiers were shooting everywhere. We wanted to run out of the house, but the soldiers from the street opened fire at the gate to prevent people from escaping. At 12 noon our house caught fire. Also burned a house nearby at 24 Buzhnichi Street, where the apprentice baker N. Ainschlag was shot. For fear of being burned in the fire, all the occupants ran out of the house into the street, despite the shooting.

On the road near the theater, two officers stopped us and asked us where we were going. When my apprentice, Neyer N., a Russian-Jew, replied that we had run out of a house that had been set on fire, these officers said, “Even worse times will come for you, we will skin you alive”.

In a neighboring house not far from us at 5 Ovocova Street (in the passage between Ovocova and Buzhnichaia), the attackers killed Zygmunt Gorny, the owner of a paper store, his wife and her sister, a 12-year-old girl (meaning Genia Gorny and her sister Klara Zontag, 14 years old – website editor’s note). They were all beaten, and their moans reached our house. I heard the Polish soldiers who blocked our street shouting: “Civilians aside, only soldiers are allowed to rob.

On Wednesday, December 3, with the help of the city’s Civil Guard, I found 1 mattress, 2 sofa beds and an upholstered couch, 1 armchair and 2 upholstered chairs from the former caretaker of our house, Jędrzej Kempior (now [living at] 25 Krółowiej Jadwiga Street), which he stole after we escaped from the burning house. <...>

Abraham Mund:

“The fire in the house at 24 Bużnicza Street was set by the military in Rittle’s store. We were not allowed to leave the burning house, and Polish soldiers shot at those who tried to do so. When we were leaving the apartment because of the fire, the soldiers on the stairs were shooting on the stairs. As a result of this shooting, a certain Rinschlag, a boy of 19, a soldier, was killed.”

Pinia Posthorn:

“November 22. At 10 a.m. seven soldiers with the identification marks of the Polish army rushed in, followed by railroad workers and then a crowd. In front of the house stood an officer on horseback. The attack was of a purely anti-Semitic character: The robber soldier said: “We have this order because you cut off our ears”.

On November 22 in the evening the caretaker [of the house] came and said that she was taking away her trunk because the legionaries had told her that they would set fire to the house and that she, a Catholic, must flee (…).

On November 22, at 11 o’clock, I saw through the window that the remains of manuscripts from the synagogue were scattered in front of the synagogue, and two officers arrived on a harness. They watched for a long time as the legionnaires and armed civilians kicked, burned and shot at these remnants [of manuscripts].”

М. С:

“On November 22, between 1 p.m. and 2 p.m., my wife’s brother, with his head already shot through, ran into the kitchen shouting, ‘My father has been killed, I myself am dying!’ At the same minute three Legionnaires came running in with the cry, “You are still alive!” and shot him several times so that Z. L. instantly gave out his breath. Then shot at Y. M. and mortally wounded him. One of these soldiers attacked the witness with a saber and hit him so hard in the groin that he fell to the ground unconscious, and when he got up he was beaten with the saber. Another soldier attacked his wife and beat her so badly that she still can’t move her arm”.

Г.:

“After the robbery, Mr. G.’s family was driven into a room where they threw a hand grenade, which left two dead and [another] four seriously wounded. The soldiers closed the room and tried to start a fire there with a broken burning lamp”.

Adolf Finkelstein:

“A soldier standing at the exit [of the apartment] saw a watch on Ignacius Landes’ hand and asked the colonel, ‘If I need this watch, may I take it, Mr. Colonel?’ When the colonel gave him permission, he told Landes to put the watch on his (the soldier’s) hand. When I complained to the non-commissioned officer, he sent me to the colonel, and the colonel said to me, “For you I am no longer a colonel, for you I am an executioner.”

Mania Frauenglas:

“On November 22, 1918 at 11 a.m. three Legionnaires entered her apartment. The victim, together with her husband and children (3), fled to her neighbor Markus Krebs, leaving her maid Marya Semenko at home. The Legionnaires robbed everything, telling the maid, “This is Jewish, you can take it.” They took many things and when they saw more goods (linen) they left, and then at 2:00 p.m. they entered the apartment accompanied by other soldiers and women. They took everything from there and loaded it onto carts. When my husband [Meshulem Frauenglas] assumed that they had already left, he entered the apartment, and soon I heard my husband crying, asking the soldiers to leave him the rest of his belongings because he had small children. Then I heard a gunshot and saw my husband run out and show me his shot hand. However, no sooner had he reached the neighbor’s door than he was shot again in the head. Then one of the soldiers came to me and said that he would take my husband, who was badly wounded, to the hospital of the Technical University. Indeed, a cart with a doctor arrived and my husband was taken away.

The next day when I arrived at the Technical University, the clerk’s office told me with a laugh, “He’s already dead.” When I cried, people laughed. <... >

The maid <...> turned to one of the [attacking] soldiers and asked him to order the others to stop looting. To this he replied to her: “I can’t do anything to them, they are allowed to loot for two days”.

Jozef Rapp:

“They said they had orders to kill and rob Jews. They said that they had killed 20 Jews. The victim assumed that the 2nd patrol came specifically after him because they immediately called him by name and demanded the keys to the cash register, which they were not given. The victim also confirms that Levin was killed by Polish soldiers who were at his [home]. The reason was that he did not give them as much [money] as they demanded.

Salomon Diesendorf (December 10, 1918):

“On November 22, 1918, from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., there were about 10 groups that moved from apartment to apartment. Each attack lasted at least half an hour. They threatened to shoot us ‘like dogs’ and were armed with rifles and revolvers. One of the groups stated: “We have already killed 50 Jews.” Some were looking for weapons, some were looking for hidden Ukrainians. I remember that one [of the pogromists] reported that he was a Krakow legionnaire and [came to Lviv] because the Jews in Przemyśl were shooting “specifically all the Jews.”

Laura White (Vaituvna), Lviv, November 28, 1919

“On November 22 around 8 a.m., or maybe even earlier, about 20 Legionnaires came to our apartment on the 2nd floor. All fully equipped, armed with rifles, hand grenades, bayonets on their sides and, without waiting to be opened, started shooting at the door. They immediately started looting. They locked [my] brother-soldier and two younger brothers in the room, beat me and my mother with bayonets and kicked me out of the apartment. When they stayed with the brothers, they started beating them, two brothers escaped through the porch to the roof, and the third was arrested. They took him to Yanovskaya Street and wanted to shoot him, but they limited it to beating him. He was beaten so badly that he lost consciousness.

All underwear and dresses were stolen from me and my family, and all tools were destroyed. The fabrics we took from the store and kept in the apartment, worth about 10,000 kroner, they threw out the window into the street. What they did not take with them they distributed to the crowd. At the same time they killed the owner of the house, [Salomon] Langnas, his son [Zygmunt], and the brother of his son-in-law, Mr. [Izydor or Jozef] Mezuzogo. They robbed the whole house and all the inhabitants, and set the house itself on fire. They had a canister with about 8 liters of kerosene, which they kept at the entrance and in the apartment, and they lit it with matches and started the fire. According to my brother Jakub Veit, who served in the army for 4 years, they were legionary soldiers.

One of the attackers was my brother’s friend from the army, from the 19th Landwehr Regiment. He was with him in a unit in Lviv in 1918. My brother asked him to intercede, and he replied, “I have nothing, I also want to get something [from the looting]” and my brother himself shouldered his belongings.

These soldiers had Legionnaires’ caps (matzevki). That’s what they said: “We had to kill these Jewish women and deal with them”. In the same building on the third floor lives a Catholic woman whose apartment they entered. When she introduced herself as Polanska and said that she was Polish, they searched [her] apartment thoroughly, thinking that Jews were hiding in her apartment. Wesner, a 50-year-old Jew, was hiding there. They discovered him and wanted to kill him, but because of his daughter’s screams and pleas, they let him go, mutilating him. They did not cause any damage to Polanska.

I had a nervous breakdown from fear, and I am still suffering physically and mentally. (I was with Prof. Orzechowski, a neurologist). After this robbery, gangs of soldiers passed by [the house] all day long. Some took clothes off my father, others took clothes and shoes even off the corpses at Langnas. These robberies were so numerous that I do not remember the number of them.

That is what I have testified and can attest to even under oath in a court of law.”

Laura Vaituvna. Her brother, who was present during the events described, confirms the content without changing it. I wrote it down carefully, Vaituvna signed with great difficulty and effort, trembling with her whole body. Dr. Abraham Landes.

Original document (pp. 22-23, 27)

Rose David:

“On November 22, 15 Legionnaires broke into my apartment and warehouse and took away by car the goods, all the equipment, underwear, clothing, silver, gold and provisions. Strong suspicion fell on the maid, who escaped to the Legionnaires and took part in the robbery with the caretaker. My husband was killed and robbed in the street.”

Laura and Antonina Pöntek (December 4, 1918)

“On November 22, a gang of armed soldiers broke into the house at 10 Krakowska Square, who inhumanely abused all the inhabitants of the house and completely robbed all the apartments. Among the robber soldiers we met the son (…) of the butcher (…) who cut meat on Krakowska Square at the city bazaar: Karczewski. We also saw how at about <...> midday, the aforementioned Karczewski, demanding “money for the Polish legions”, killed Mr. Mojzesz Agid with four shots. We are prepared to repeat this testimony under oath.

Rachel Tashman:

“The apartment of Ms. Rachel Tashman, who lived on Tzibulna Street, was completely burned down in a pogrom on November 23 this year, and her mother was shot dead.

The applicant herself was wounded on November 14 this year (gunshot wound to the stomach) and remained in a general hospital until December 21. The applicant had no means of subsistence and was therefore unable to pay for the doctor’s services. As the applicant is still very weak and has not yet fully recovered, the medical commission advises that a doctor should be sent to the applicant currently residing at 18 Zamarstynovskaya Street”.

Adele Neuer:

“On November 23, 1918, at 9 a.m., three Legionnaires came in. One of them had a red and white badge on his shoulder, he was tall, strong, with a weathered face with a cut on his face. This is the one who killed my brother. <...> They broke the windows in the door and demanded gold and silver under vile insults. My brother gave them everything. The above-mentioned man grabbed my sister-in-law (my brother’s wife – website editor’s note) with a strong hand and then took away her jewelry and money hidden on her chest. After taking these valuables, he started hitting her in the face with a gun so that her upper teeth were hanging down in her jaw. He threatened her with the revolver. When the husband asked him to stop beating his wife, he began beating his mother, his sister-in-law’s old lady, and cut her side. He then went out on the porch and shot his brother through a broken window, pointing the rifle at him. I would like to point out that a second soldier standing in the room was holding my brother so he could not hide. When my brother was mortally wounded in the stomach by a bullet, he shouted: “Fuck!”, the Killer answered him, “Son of a bitch, you are still screaming, I will give you another bullet”.

At the last moment, the brother waved for the children to leave and gave up his breath. The killer stepped on him mercilessly, took off his wedding ring, and started smashing cabinets. And began hitting the children to keep them from screaming. At the same time, he put a revolver to his sister-in-law’s temple, telling her she still had money. Then my 14-year-old niece started to lead him around the room, asking him to take everything away so she could save her mother. <... >

The third stood at the porch door, making sure no one left, and kicked a 6-year-old child in the side, threatening to shoot him. My sister-in-law and I hid in the attic. The three legionnaires then went to the landlady’s apartment, where my brother’s killer sat down and played the piano beautifully (so intelligent!) for about an hour and a half, both of his companions dancing. Apparently the murderer was an intelligent man from the upper class, as I, who played the piano, found the playing interesting. Then they went up to the second floor where there were many women from whom they took away gold, valuables and money. Another old man, a Jew with a gray beard, they wanted to shoot, but his daughter covered him. The Legionnaire ordered her to open her mouth, and shoved a Browning between her teeth, keeping his finger on the trigger.

Then they returned to our apartment again, and the killer trampled the body of my brother, whose clothes and body bore traces of this abuse. I would like to note again that my brother begged the killer to spare him and his children, as he had only returned from Russian captivity 6 weeks ago and was even wearing military pants. We kissed his hands and feet, but he pushed us away, saying: “It’s a pity to leave such a strong man behind, we should kill him.” They took off his watch and chain.

Eliash and Natalia Sobel:

“An officer declared at 4:30: ‘We will avenge your Jewish militia, we are from Krakow, we hate Jews. We want to kill them all like dogs.” The behavior of the bandits was simply indescribable. The father of the family was mercilessly beaten, which was also an indirect cause of his death. The daughters, who tried to protect him from the blows, were insulted with harsh words, not sparing blows with the butt of a gun. When [our] acquaintance Vladislav Cholek from Romanovicha Street came the next day to take the beaten and robbed people to his house, the Legionnaires [did not let him in], threatening him with rifles. The stolen items were taken away by car.

From the letterьма Jewish Committee for Assistance to Victims of Riots and Robberies in Lviv:

“On December 18 of this year (1918 – editor’s note) in the afternoon, Osyash Rokah, who lived at 4 Elephant Street, was walking along King Louis Street. An officer on horseback was passing along the road. Suddenly the officer called out to Rokah, and when he approached him, he hit him in the face with his whip for no reason”.

From the report of Judge Zygmunt Rymowicz of the Supreme Court of the Polish Republic:

“The corpses were already there on the morning of the first day [of the pogrom, November 22, 1918]. I won’t describe all these scenes. People were simply victims of atrocities. <...> On one of the main shopping routes along Krakowska Street, running from Market Square to Pl. Krakowska, practically all the stores were looted.”

The text is by Grzegorz Gauden, Lwów – kres iluzji. Opowieść o pogromie listopadowym 1918 (Lviv. End of illusions. An account of the November 1918 pogrom). Kraków, 2019.

Rafal Buber, attorney for the Lviv City Council (January 2, 1919):

“I have taken the floor to call the attention of the Honorable Council to what is happening in the Jewish Quarter. By unanimous resolution the Council condemned the terrible and bloody pogroms which took place on November 22 and 23. However, we should not think that the pogroms are over. I can say with absolute certainty that the pogroms continue, that there is not a day, night, hour or minute when there is not another Jewish pogrom.

<...> The cases that first come to my mind are those in which Jewish citizens are caught in the street ostensibly to be sent to forced labor. In the middle of a white day, army squads stop all passing Jews on the street, especially in the Jewish neighborhood, regardless of their age, condition or health. This kind of catching takes place every day in several parts of the city, despite the fact that the headquarters has issued an order forbidding this kind of forcing people to work.

<...> The second type [of bullying against Jews] are searches of Jewish apartments, which are accompanied by robberies, insults, and sometimes dishonoring of women, etc. <...> At 14 Sykstuska Street, an army detachment led by an officer conducts a search. They find two revolvers in the possession of a Christian resident; they find no weapons or other suspicious things in the possession of Jewish residents. And what happens? This Christian resident remains at large, while all the Jews are arrested and only by order of headquarters are released 24 hours later. Moreover, half an hour after this squad leaves, the same squad or another squad returns to this house and demands a ransom in money or in kind from the remaining women.

<...> I could list such cases endlessly. This medieval system [of searches] causes terrible resentment among the Jewish population and cannot be tolerated any longer. I would like to draw your attention to the fact that General Rozwadowski explicitly forbade searches from 4 p.m. to 6 a.m.. Despite this, such searches take place continuously every night in dozens of streets.”

Proceedings of the Jewish Committee (January 26, 1919):

“In a clear assessment of the events one cannot speak of a single pogrom, we are talking about a series of pogroms that continued uninterruptedly for 6 weeks (from November 22, 1918 to the beginning of January 1919 – site editor’s note), which were repeated every day and every night with systematic, programmatic regularity, albeit in different forms and increasingly different, new kinds.”

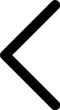

Victims

Judge Zygmunt Rymowicz of the Supreme Court of the Polish Republic, who headed the Extraordinary Governmental Commission of Inquiry to investigate the pogrom in Lvov, estimated the number of those killed on November 22-24, 1918, at about 50. At the same time, the Jewish Committee, which had collected 1,700 questionnaires from victims of the pogrom, provided him with a list of 73 murdered Jews. The writer Andrzej Strug estimated that the number of those killed in the Lvov pogrom reached 960. Grzegorz Gauden, author of a book about the pogrom, who has studied all available archival documents, considers this figure to be the closest to the truth.

But the abuse of Jews in Lvov did not end on November 24, 1918. In total, according to the estimate of the Jewish Committee, the pogroms in the city for two months (from November 22, 1918 to January 26, 1919) affected 20,000 Jews, that is, about one-third of the Jewish population.

The list of victims, which includes the names of 99 people killed during the pogrom, 102 victims on November 22-24, 1918, and another 94 victims during the continuation of the pogrom (mainly in December 1918-January 1919) , is based on documents kept in the Polish archive Karta, Grzegorz Gauden’s book “Lviv. The End of Illusions. An account of the November 1918 pogrom” and documents published in the “Testimonies” section.

Executioners

Polish soldiers

Polish soldiers

The start of the pogrom in Lvov on November 22, 1918 was given by Polish soldiers who, in the presence of their commander, Lieutenant Roman Abraham, and in front of the gathered crowd, began to smash Zipper’s jewelry store, the largest and richest store in the city, in the Market Square. For military and civilians alike, this was a clear sign of the legalization of looting and violence against Jews.

In their testimonies, the victims of the pogrom named among its active participants Colonel Skrzytuski (who led the pogromists during the robbery of Moses Parnes’ apartment; after the robbery was over, he drew up a report on the stolen goods), Stefan Duda and Kazimierz Kielbaszewicz from the Polish Legion, as well as Jan Banderowski (who led a Polish army patrol), soldier Chrzanowski, thief Jozek Czarnecki, one-legged bandit Nadgorski, and the butcher’s son Karczewski.

According to various eyewitness accounts, including that of attorney Tobias Ashkenaze, founder of the Jewish Committee for the Victims of the Lviv Pogrom, Red Cross nurses were also directly involved in the crimes. According to Ashkenaze, a total of 14 nurses were involved in the pogroms. Sali Zonntag, a resident of Lviv, recalled that one of these nurses called on the soldiers to shoot her relatives during the pogrom. In the end, the pogromers killed her older sister and her husband and her younger sister, who was only 14 years old.

The argumentation of the pogrom participants was that during the Polish-Ukrainian war, which began on November 1, 1918, Jews allegedly occupied the Ukrainian side, shot at Polish soldiers and poured hot water on them. Similar accusations were contained in a proclamation by the Polish commandant of Lvov, Czeslaw Monczynski, which he published on the second day of the pogrom, November 23: “During the three weeks of the struggle for Lvov, a significant part of the Jewish population not only did not remain neutral towards the Polish army, but often resisted with arms in their hands and treacherously tried to stop the victorious march of our troops. Cases of shooting our soldiers from ambush, pouring boiling water on them, throwing axes at patrols, etc., were established.

The rioters told their victims that they were allowed to rob and kill Jews for 48 hours. The acute phase of the pogrom, when people were beaten, maimed, killed and burned alive, as well as looted, lasted a little longer than that, from the morning of November 22 until November 24, 1918.

Sources:

- Grzegorz Gauden, Lwów – kres iluzji. Opowieść o pogromie listopadowym 1918 (Lviv. End of illusions. An account of the November 1918 pogrom). Kraków, 2019.

- Documents published in the Evidence section.

Czeslaw Jan Monczynski

Czeslaw Jan Monczynski

Czesław Jan Monczynski was a Polish military and political figure, colonel of the Polish Army, and Polish nationalist. He was personally responsible for the pogrom in Lviv, which lasted more than two days in November 1918.

He was born in 1881 in the family of a folk teacher. In 1908 he graduated from the Faculty of Philosophy of Lviv University, during his studies he belonged to the Lviv military organization “Bartosz’s Detachments”. In 1910 he began working as a teacher of Polish, Latin and Greek languages.

When World War I broke out, Monczynski was drafted into the Austrian army, where he was first appointed a battery commander, then a lieutenant and captain in the reserve. After demobilization, he worked as a philosophy teacher at a gymnasium, and at the same time as commandant of the Polish military staff in Lviv, which was part of the General Staff of the city’s defense. During the Polish-Ukrainian war from November 1 to 22, 1918, he served as the chief commandant of the defense of Lviv, when there were heavy battles between Poles and Ukrainians for the city.

From November 22 to December 12, 1918, Monchinsky was commandant of Lviv and Lviv district. The pogrom in Lviv was started by his subordinate, Lieutenant Roman Abraham. On the same day at dawn, his soldiers hoisted the Polish banner at Lviv City Hall, and then, in joy, smashed the most expensive jewelry store in the city – Zipper’s store. For the military and the crowd, this was a clear reason to loot and abuse the Jews. At 9 a.m. on November 22, when the pogrom had already begun in Lvov, Monchinsky arrived by car in the city center. On Market Square, he watched the actions of the pogromists with a smile and did not hinder them in any way, recalled Maciej Rataj, one of the eyewitnesses. “I cannot forget and forgive him that day and that smile!” he wrote.

A few hours after the pogrom began, the leaders of the Jewish community, Dr. Ozayas Wasser and Dr. Emil Parnas, arrived at the commandant’s office in Lvov, asking for protection. They brought with them an order from General Boleslaw Roy, head of the Polish army in Eastern Galicia, to immediately impose a state of emergency and courts-martial in Lvov. Monczynski ignored this order, kicking out Vasser and Parnas. According to one version, he behaved this way because the Jewish delegates did not show him enough respect or joy that the Poles had regained control of the city. This was overlaid by the colonel’s personal grudge against General Roy, who at one time did not appoint him commander of the operation to liberate Lvov.

A few years later, Monczynski confirmed that during the pogrom, Wasser and Parnas had indeed handed him a letter from General Roy, but, according to him, it was not an order, but “just an ordinary letter intended for the appropriate authorities.” He went on to write irritably that these “interested” persons began to “make demands” to protect the wealthiest Jews and Jewish homes from “the possible anger of the [Polish] people.”

This was also stated in the first proclamation of the commandant of Lvov, which he published the day after the visit of the Jewish delegation, November 23. It claimed that the command of the Polish army “suppresses the natural impulse of the Polish people and army” to take revenge on the Jews because “all citizens, regardless of religion, have been placed under the protection of the law.” But, in fact, this proclamation, in fact, justified the actions of the pogromists: “During the three weeks of the struggle for Lvov, a significant part of the Jewish population not only did not remain neutral towards the Polish army, but often resisted with arms in their hands and treacherously tried to stop the victorious march of our troops. Cases of shooting our soldiers from ambush, dousing them with boiling water, throwing axes at patrols, etc., have been established.” No evidence of such unfriendly actions on the part of the Jews was given. But some of the pogromists repeated these accusations word for word (both about boiling water and axes), it follows from the testimonies of the victims.

Monchinsky’s new order to introduce military field courts, which provided for the death penalty for criminals found guilty of robbery and rape, appeared only two days after the beginning of the pogrom, on November 24. The commandant had to sign it because of increased pressure from the military authorities. But by that time hundreds of Jews had already been killed, thousands wounded and robbed, and the entire Jewish quarter of Lvov, along with the ancient synagogues, was almost completely burned.

Despite a great international scandal because of the many victims during the Lvov pogrom (according to some estimates, 960 Jews were killed), Monczynski managed to create a myth about the heroic defense of Lvov, how local Polish units selflessly fought the Ukrainians until the arrival of reinforcements from Krakow. At the same time, the commandant called the main enemy of the Poles not external forces (Ukrainians), but internal ones, i.e. Jews. In his memoirs “Boje Lwowskie” he wrote that in November 1918 there was no pogrom in Lvov at all. At the same time, he and his subordinates were engaged in “a real struggle with an enemy a hundred times worse than the external one”.

A few years after the end of the pogrom, Monczynski was appointed ambassador to the Sejm of the Polish Republic, and was awarded the highest military award, the Virtuti Militari, for services in the Soviet-Polish war.

Sources:

- Grzegorz Gauden, Lwów – kres iluzji. Opowieść o pogromie listopadowym 1918 (Lviv. End of illusions. An account of the November 1918 pogrom). Kraków, 2019.

- Czesław Mączyński, Boje Lwowskie. Warszawa, 1921.

- Documents published in the Evidence section.